To see things as they really are: one of life’s most elusive challenges, whether in love or politics. It’s a recurring theme in Great Crossing as Richard and Julia make choices based on how they want things to be. I think the same can be said for all of us, some two hundred years later. You see, creating a narrative allows us to hide fears, save face, beautify the plain, justify the ugly. And there’s a lot of story-telling going on right now about Juneteenth. Here’s another.

I’m a little girl in the back seat of a 1961 Impala, sliding around with my little brother on the vinyl because nobody wore seat belts yet. We’re headed with our big itchy army blanket, faded towels and floppy picnic basket – the beat-up one that makes me embarrassed – to Galveston from our little house with the peeling paint in Houston. The way our dad drives, we get there in under 45 minutes, It’s June 19, 1965, a Saturday and a hot one, with giant clouds that just don’t seem to block the sun enough for my mother’s liking. Once we get to town, there’s a parade going on and the air smells of barbeque and deep-fried shrimp and our mouths water. “Cain’t we buy some food in town, Daddy?” I ask. The answer is so obvious, he didn’t give me one. My brother and I see some kids smaller than we are on tricycles in the parade. Everybody’s dressed up. Everybody looks different than what we are used to seeing in our neighborhood, because they are Black and have their own place to live. We don’t stop to watch because it’s not for us to enjoy, this parade. “Juneteenth,” our mom says, “I forgot about that, and all the traffic. Think we can find a place to park?” But down a-ways from town and the good smells, there are plenty of places to park.

Now, swimming in the gray-blue waters at Galveston beach means swimming in a warm, salty bathtub called the Gulf of Mexico, watching out for stinging jellyfish, and constantly emptying heavy wet sand from the bottom of our swimsuits with much potty-hilarity. When the wind changes, the sweet smell of cookouts gets ruined by the rotten egg stench from the sulfur digs down the coast. And we’re already so used to the oil refinery smoke, we think it’s just an extra layer of barbeque fumes. Not one person is celebrating Juneteenth on our neck of the beach, full of families like ours with their own little plot of sand staked out by blanket, towels, picnic baskets, and skin color. Nobody seems to be having the kind of fun the people downtown at the parade are having, but nobody’s unhappy. Just not party-happy, parade-happy.

“Why can’t we have Juneteenth?” I asked, thinking about the kids on their trikes. Dad, who I much later discovered had majored in history, said, “Because it’s not about us. Come to think of it – here’s a coincidence – it was a hundred years ago on this very day, General Granger landed here in Galveston to tell the slaves they were free.” “What’s a slave?” “Somebody who has to work hard for nothing.” “I heard you tell mommy you work hard for nothin’ at the mental hospital.” He laughed. “Yeah, but someday I’ll get paid when I’m done being an intern. And nobody owns me or beats me, like they did slaves.” My brother and I were still a long way from seeing things as they really were, but we got an introduction to a past we never knew existed.

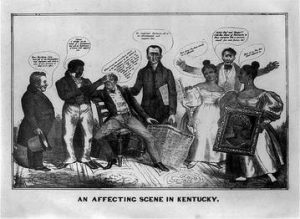

Kentucky, as a border state, did not consider their enslaved peoples as legally freed until six months later, when Congress passed the 13th Amendment in late December 1865. General Gordon Granger went home to Kentucky; he’s buried in Lexington. The 13th Amendment was not officially recognized by his state’s legislature until 1976. In 2005, Kentucky’s lawmakers made Juneteenth a holiday, although it seems only a few predominantly Black communities acknowledged it. In February 2021, the board of directors at Georgetown College, down the road from Great Crossing, passed a resolution to recognize Juneteenth, describing it as an effort toward inclusion and kindness on campus.