Richard was born October 17, 1780, and almost didn’t make it to his thirty-third birthday.

In its earliest drafts, Great Crossing opened with the origin of Richard’s fame: on the glorious morning of October 5, 1813, along the River Thames in Ontario, Canada, where fighting men credited him with slaying the greatest Native American leader ever, Tecumseh. But early readers pointed out the fact that I had framed this as a love story, and they didn’t have much interest in the fighter or his battle. Nobody cared much about the War of 1812. Besides, wasn’t that in Russia somewhere with Napoleon, and weren’t lots of cannon involved? No, I would try to carefully explain in my most enthusiastic teacher mode. This was a terribly important war, like the second American Revolution! Men were being kidnapped by British naval ships and forced into serving as slave sailors! They were sinking our ships, arming Tecumseh’s followers and paying them bounties for killing Americans! This battle made Richard famous almost overnight!

None of that mattered, because in the end, all isn’t fair in love and war. Even war has to serve love’s purposes in the unfolding of a story, every single time.

No other chapter in the book endured the amount of hacking and slashing this one received, nor the insult of being relegated to the back of the book. But that’s where it belonged, where Julia and Richard shared and suffered from the experience, as any couple must, who are bound together as mysteriously as they were. No other chapter quite took on symbolically the literal hacking and slashing Richard received at that battle. This young man suffered the rest of his life for the privilege of being credited as the Father of the American Cavalry and a great war hero. It did put him in the ranks of Washington, Jackson and Harrison. It did help get him elected as part of the 1836 presidential ticket. Yet, the collective memories of those presidents as war heroes endures while Richard has faded into obscurity, along with the War of 1812.

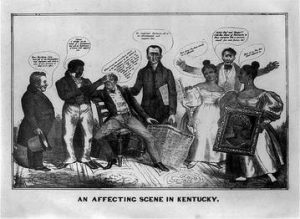

Why? The flip side of Julia’s and Richard’s simple love story is how it bogs down into complex social dilemmas. In their time, it was complicated because she was a fair-skinned slave who remained a slave, according to census records. Yet, Richard set her apart as mistress of an exquisite household and considered her an exceptional mother to their daughters. He didn’t hide her away, lie about her or their children or let the press get away with belittling them. People did not like that. It just wasn’t done in Kentucky or even in New York, for that matter, in 1813. Nor was it acceptable in 1913, and there are still places in America since 2013 where so-called mixed race relationships meet with disapproval.

So why has Richard, along with the war that made him famous in his lifetime, been relegated to the pile of forgotten names and events? I think it may have something to do with shame. After the deaths of Julia and not long after, their daughter Adaline, Richard seemed to go into a moral tailspin. Some people might say he deliberately flaunted keeping young, mixed-race slave women as his “housekeepers” in front of the critics and gossips within Washington and Kentucky society. By the time of his death, his two surviving brothers had become leaders in the Campbellite sect, and their outrage at his openly referring to a slave woman as his wife was more than they could handle. Intimidating and denying their niece, Imogene, by saying in a legal document that her father had no offspring, illustrates the depth of their indignation. Rage often has its roots in shame at what needs to be covered, or better yet, buried. And they all but buried Richard’s name and memory.

Richard became a loser. And the War of 1812, American-style? We won that, didn’t we? Not really; it was a draw. Everybody went back to the same old boundaries, with the same people suffering the real losses: the members of ancient tribes in the Americas, and the members of other ancient tribes torn from their lands in Africa.

(For an in-depth look at Richard in the Battle of the Thames, I highly recommend Dr. David Petriello’s brief biography of RMJ The Days of Heroes are Over.)